One of my favourite popular science books is ‘Mutants: On Genetic Variety and the Human Body’. In the book Armand Leroi describes various humans which, although at the time may have ended up in one of those infamous ‘freak shows’, have a selection of different deformities of varying severity. The book is illuminating in that it follows the idea that if we can see what made something go wrong during development, then it tells us something about what happens when things go to plan. Knowing what we do now about development, it is possible to look back at these historic cases and explain them biologically. For instance, if someone is born with a deformed limb, and we find that they have a mutation in a specific gene, we can say that the gene is somehow involved in limb development.

Mutations

are natural. As Leroi sates, “we are all mutants, but some of us are more mutant than

others”. However, they can also be induced. Studies of embryogenesis and

development are inextricably linked with Drosophila

fruit flies. Many facets of development were figured out by inducing mutations in Drosophila with X-rays, resulting in a bewildering number of mutants being described with

diverse and imaginative names. Individual pathways and genes have since been

correlated with particular phenotypes.

|

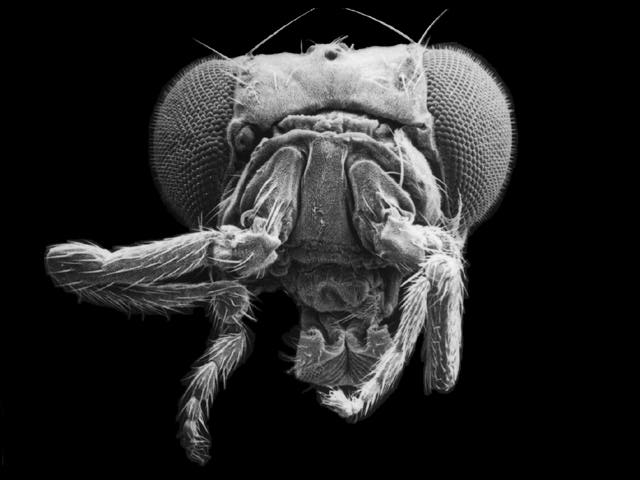

| Antennapedia mutant of Drosophila: flies possess legs in place of antennae |

Not all errors in development are directly linked to mutations. 1957-1961 saw

the tragic incident of thalidomide, a drug taken by pregnant women to ease the

discomfort of morning sickness. It soon became apparent that thalidomide was

teratogenic with the resulting offspring sometimes possessing, among other

deformities, severely stunted limbs. Clearly the presence of thalidomide

interferes with foetal development. Although it is still not fully understood,

various ideas exist about the way in which it causes the effects, including

angiogenesis in the developing limb, thus stunting outgrowth (1).

|

| A ewe investigates her Schmallenberg-affected lamb |

When all of the images of lambs with arthrogryposis started to

emerge a few months ago as a result of Schmallenberg virus infection during

gestation, it reminded me of the approach ‘Mutants’ was following. As a Bunyavirus, Schmallenberg virus only has

6 proteins. By looking into the pathways which these proteins disrupt it

could be possible to learn something about proper limb development. Whilst looking

into this a bit more, a paper has been published detailing the infection of

foetuses with Cache Valley virus (2), another Bunyavirus which also causes congenital

abnormalities in sheep.

The paper looks at the localisation of virus infection and the

time-frame of infection and subsequent development of the malformations. The

data support previous work revealing that infection of the central and

peripheral nervous systems is responsible for reduced foetal movement and the eventual

development of the arthrogryposis. This confirms the idea of using

viruses to investigate development: observation of the tropism of the virus and

correlating this to the deformities of the resulting offspring allows, at a

somewhat macroscopic level, identification of the role of particular tissues in development. As more

and more methods are developed it may be possible to elucidate the molecular

pathways which are disrupted by infection with these viruses, thus linking

development to a specific pathway. Clearly the results are likely to be more

‘pointers’ of what’s happening as opposed to precisely defined interactions,

but learning from mistakes is always a good thing!

(1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009. 106(21):8573-8.

(2) J. Virol. 2012. 86(9):4793-800

No comments:

Post a Comment